|

Have you ever mimicked someone's accent or perhaps made up nonsense "words" that were meant to sound like a specific language? Kind of like the Muppet's Swedish Chef? I was once with a group of French people who were making fun of the way Americans speak. As they were mimicking us their faces went kind of slack and their jaws and lips barely moved as they said something like "bluh, bluh, bi, bloo, bluh." What they were getting at, I think, was that Americans facial muscles tend to be pretty relaxed when we're speaking comfortably, and often our vowels can sort of morph into very similar sounds. On the other hand, when I first lived in France and was speaking French almost all the time my face hurt. I was using facial muscles more often in ways that I wasn't used to.

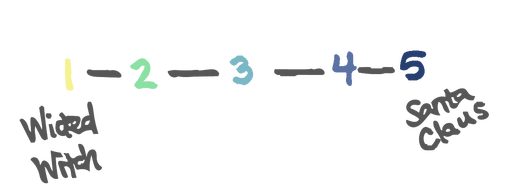

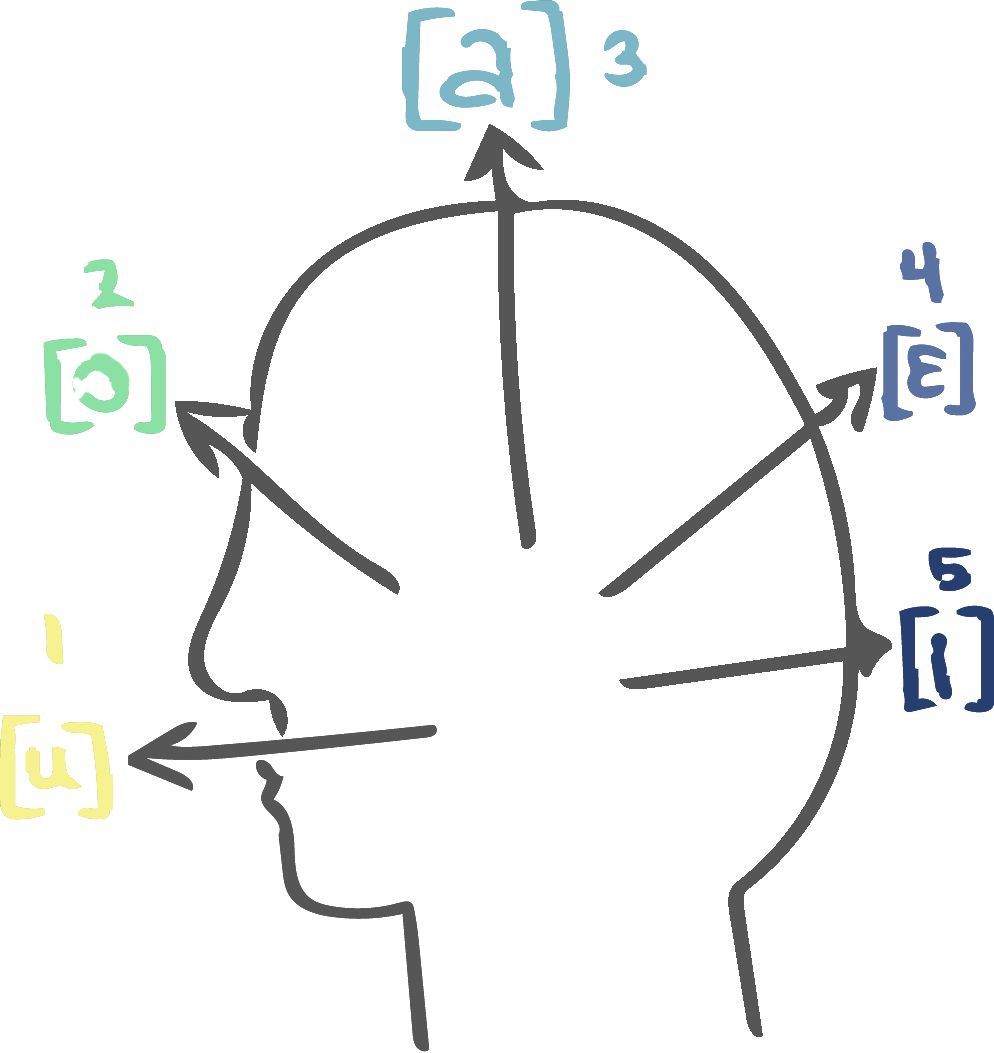

It makes sense that American English would sound garbled to a foreigner; the International Phonetic Alphabet has 30 different symbols for vowels, but Americans use at most 16 of these, and most regions use fewer. British English speakers, on the other hand, use about 20 vowels compared to our 16. So, yes, when we speak it may kind of all blend together. But wait . . . don't singers want to blend? Don't we want to develop that creamy, gooey, luscious legato vocal quality that just makes the sound luxurious? The answer, at least for classical singers, is yes, we do. But at the same time, we want to be heard, understood, and we want build up vocal stamina in a healthy lasting way. This means, then, that the key to creating a smooth silky singing voice is in steady constant air flow (see this post) and vowel equalization. First I want to talk about vocal placement. Placement isn't strictly about vowels, but understanding vocal placement will be helpful later in the post. I like to use a scale to represent forward and backward vocal placement. If you've ever heard about singing in the "mask" or anything about forward and backward singing, this is probably what it was referring to. I find the easiest way to explain it is that forward placement sounds like the Wicked Witch--"I'll get you my pretty!" When speaking or singing this way you'll probably get some sympathetic vibrations in your nose and cheek bones. Backward placement sounds like Santa Claus--"Ho, ho, ho! Merry Christmas!" This may feel like you've got a frog in your throat. Neither of these vocal placements are correct--they are simply the extremes. Correct placement is in the middle somewhere. Once you've established these two extremes (I'd recommend just practicing with your speaking voice first) you can play around with the degrees of forward and back, basically every placement in between.

There are more than 5 possible placements with micro-degrees of change, but 5 is a good amount to figure out and master when you're playing around--and it lines up well with the vowel placements I want to talk about.

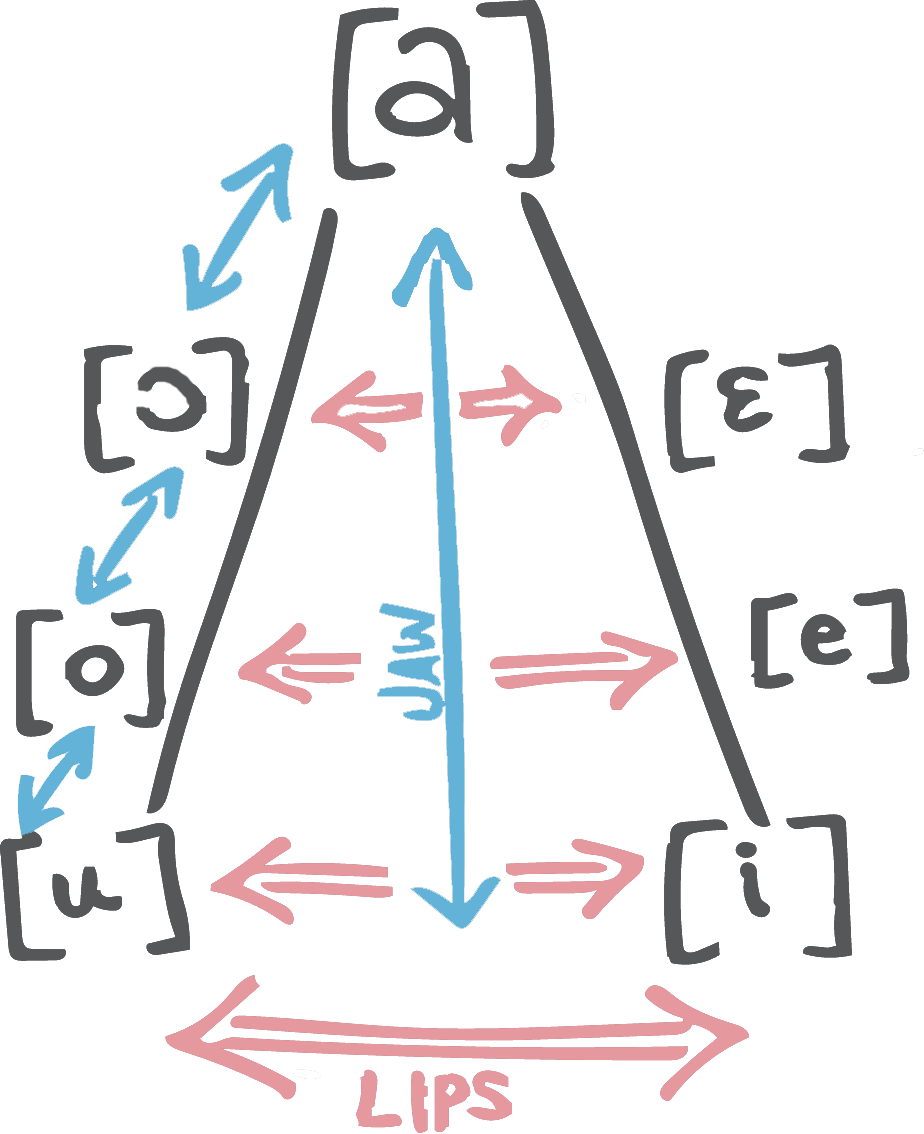

Now on to the vowels. There are more than the five or six that I want to discuss, but these will do for today. In the International Phonetic Alphabet [a] = "ah" as in hot, [ɔ] is "oh" sound as in chores, [ɛ] is "eh" as in bed, [e] is "ay" as in way, [u] is "oo" as in shoe, and [i] is "ee" as in tree.

I've said before that I was a really hard student to work with, right? Because I needed things explained so many different ways before they clicked? So, the following explanation is really the marriage of things I learned from several different teachers.

So, how can you fix this? First, you can think of sending your vowel in the opposite direction than the way that they "want" to go (send your [u] forward towards a 1, and your [i] back towards a 5). Ideally all of the vowels then end up in the same place in the middle--I personally "feel" that this placement for me is between my molars. All of my vowels should "land" there. Another way to get all of your vowels into the same placement is by singing vocal exercises that switch quickly between two vowels; this will help bring the two vowels to the same placement, thus "equalizing" them. There are some vocalizes in the materials section of my website that you try if you want (here).

This chart gives a more detailed explanation of how the vowels should be formed. notice that the vowel "opposites" of [i] and [u] use only the lips to change back and forth between the two. The jaw and tongue shouldn't move. They don't need to move. Try it and see. When you're moving smoothly between the two you might feel like you're saying "wee." [o] and [e] are the same, only lips involved. They become "way." Now, if you then want to equalize [u] and [o] for example, the lips stay in the same place and only the jaw needs to move. This then becomes "woah" when sung smoothly. [i] to [e] becomes "yay." If you can master this sort of vowel equalization you will have mastered the most efficient way to create legato. You will have also eliminated any tension that may come from vowel formation and increased your vocal endurance. It takes practice, but it's definitely worth your time. Happy practicing!

0 Comments

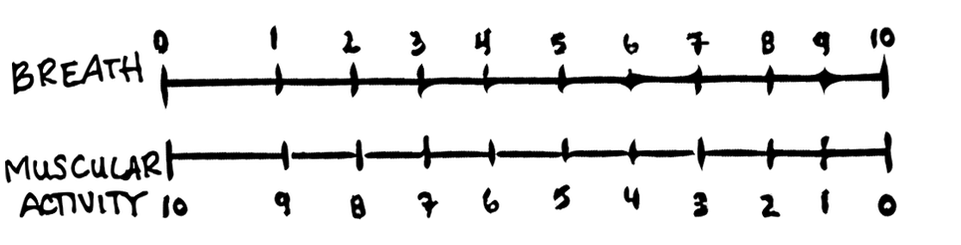

I mentioned these in an earlier blog post about auditioning, but coffee stirrers are an amazing vocal tool. You need one that's basically a little straw, and the single tube (rather than the red double-tube kind) work best. Using one of these in your singing practice can help improve your legato, increase vocal stamina, and keep things quiet if you don't want to disturb anyone. But today I'm going to mostly talk about how it can help you improve your vocal range and avoid injury. First, you should understand a little bit about how vocal sound is produced. In your throat is a little box made out of cartilage called a larynx. This houses your vocal folds which are also surrounded by small connective ligaments and muscles. When you send air through these folds the rapid air flow decreases the pressure between the two folds and draws them together (Bernoilli's principle. The same thing that makes airplanes fly. Interesting, huh?). When the vocal folds are drawn together, they vibrate and create a buzz sound; these sound waves bounce around in your throat and mouth and when they make their way out--ta-da!--you've vocalized. So here's the thing; rather than simply allowing the fast flowing air to draw the vocal folds together, you can use the small muscles in/around the larynx to manually manipulate the vocal folds. You can actually "slap" theses folds together. Think about the last time you were yelling, especially in a crowd, maybe at a sports event or concert. Did your throat feel sore? Did speaking the next day hurt or feel uncomfortable? You were probably slapping your vocal folds together. It's very easy to resort to this sort of "slapping" technique when attempting to sing loudly. Most precocious young singers will resort to this to some extent. What's the problem with this? Well, besides the fact that the sound quality will always be at least a little forced, you're actually in danger of permanently damaging your delicate little vocal folds. Slapping them together can create a sort of blister and callous on your vocal chords (called polyps and nodules). Remember what I said about precocious young singers? Julie Andrews was pushed into serious vocal training very early and she didn't avoid the slapping/straining stumbling-block. She developed vocal nodules; the surgery to removed the nodules didn't go well and permanently damaged her vocal folds. Now, back to the straw. The straw can help you avoid vocal damage AND improve your vocal range, for the same reason: It helps you to create a constant, reliable air flow. If you look at my little diagram below, I've tried to visually represent the inverse relationship between breath and muscular activity in creating buzz tone. If your breath is 10 and your muscular activity is 0, you're just exhaling. If your muscular involvement is at a 10 and your breath flow is 0, you feel like you're choking. Actual sound production is somewhere in the middle where both air flow and muscles are involved. If you have a tight, pinched, or strident sound and have trouble singing in your upper range, you are likely too high on the muscular scale and too low on the breath scale. Vice versa, if your sound is breathy and weak, the air flow is probably too free, not fast enough, and your muscular activity too low or unengaged.  What does the straw do? It basically ensures the balance between the two, and is especially good for those who sing with too much tension on high notes (this is why it can instantly "increase" your range; It really just overrides your bad muscular habits so you can access your potential singing range). By singing through the straw you've created an external monitoring system for air pressure and constant airflow.

Here's how to do it:

Don't be afraid to really push your upper register, just make sure that the airflow never decreases. If you feel the airflow drop or skip you know you've reached a problem area. You have poor muscular habits in this range and you need to really work with the straw to overcome them. Slides and sighs are great for this. Singing with the straw is a great way to sing through your actual repertoire as well. It gives you an opportunity to sing through in a very non-stressful (for your larynx) way. You won't have any bad diction habits that are messing with your placement or adding tension. When you're singing through repertoire you can alternate phrases with the straw and singing on "sha" or something. Now is a really good time to learn to "feel' singing rather than listening to your own singing. Obviously the sound is going to be different because you're singing through the straw. But it should also feel different. Ask yourself how. How does this feel different? And how can I reproduce this feeling when I'm singing without the straw? Because that's the goal. Just practicing with the straw will train new muscle memory. But this exercise will be much more effective and work more quickly if you take the time to analyze it. Have fun practicing this week!

Since finding out that Emma Watson had been cast I knew I was unlikely to get an interpretation as lovely as the Broadway or London Casts’ stage productions (the original London cast is the best version of the Disney musical out there IMO). Which was unfortunate, since this ↓ is truly lovely. Sadly, "Home" didn’t make it into the movie other than as part of the background music. ☹

And that makes me frustrated for so many reasons. I’m frustrated that Disney won’t stand behind their choice of Watson and let her voice be her voice. It makes me mad, because it’s teaching young girls that their voices have to sound processed to be beautiful (read more on my opinion about that here). And I’m annoyed that Disney thinks they have to cast someone who is guaranteed to send those money-spending millennials to the movie theater rather than having the confidence to hire someone with less name recognition but more singing experience and stand behind their quality of work. It’s like an artist who screws up a drawing or painting but says “Oh well, I’ll just scan it and fix it in Photoshop.” But the Photoshopped version is no longer a painting. Duh. Over-processing a sound is just as glaring as an over-processed image if you know what to listen for. And after reading this, you’ll know what to listen for.

First let’s begin by listening to the opening song from the other two Disney versions. The first is the animated movie. The singer is Paige O'Hara, a Broadway actress. Try listening for slight pitch variations. Nothing truly out of tune, but little dips and shimmers. If you can’t hear that yet, no worries. Slight differences in pitch can be hard to pick out if you’re not used to it. Listen to the longer notes especially. If you know what vibrato is, that’s an example of very slight pitch changes. Scooping or swooping sounds are hitting a pitch slightly flat and then raising the pitch to be in tune.

Now ask yourself where it sounds like she’s singing (she’s obviously in some sort of recording studio situation, but what might the shape of the room look like? Can you visualize it from the sound? I’m asking you to use your "bat sense"). Outside? Inside? In a long hallway? In a small room? Large room? Room with a high ceiling? In her car? In the shower? The second recording is Susan Eagan from the original Broadway cast. You hear the difference right? You may not be able to quite put your finger on it, but it’s there, right? Ask yourself the same questions—do you hear pitch variations? Where is she singing? If you’ve got time, switch back and forth between the two and try to really identify the differences between them. You might mostly notice how long they hold out the notes or the way the pronounce the words. However, try to really use your "bat sense" again and hear the difference in the sound quality.

Right, so where does it sound like these singers are singing to you? If I were to describe it, I’d say that O’Hara’s version sounds like she’s in a small carpeted room, more or less. She’s got kind of a light, “thin” sound, like there are no hard walls or anything for the sound to bounce off of. She even sounds a little like she may be outside, where again there would be no walls for the sound to bounce around on. Eagan’s recording sounds like she’s in a bigger room; it’s a little more reverberant like maybe there’s a tall ceiling where she is, or a long empty hallway (not literally, but do you get the idea of describing the sound?).

All right, now let’s move on to Emma Watson’s version. Again, listen to pitch, especially on the long notes (though there aren’t many of them in Watson’s version). Ask yourself where it sounds like she’s singing.

Okay, okay, doesn’t it sound like she singing in the bathroom? I mean, seriously? Do you hear that? That’s called reverb, short for “reverberate” and it’s extremely common to add it to modern popular music. So maybe it’s a quality that just jumped out to you as “modern.” But the thing is, it’s not real. No human voice actually sounds like that. It’s possible for the human voice to generate its own quality of depth—that’s what singers study for years to learn how to do well without damaging their voices. It’s the mature sound quality in the first two examples. But if you want to make a thin voice sound more “mature” and resonant, you can artificially add reverb. And there’s a lot of reverb when Emma Watson sings in Beauty and the Beast. I especially notice the difference as the rest of the cast enters in singing “Bonjour! Bonjour!” Their sound is dramatically less touched-up.

And what about pitch? Doesn’t Emma Watson have the most wonderful accurate pitch EVER? She’s so good, her pitch is purer and more flawless than either of those previous examples we listened to. And that’s once glaring indicator that Auto-Tune has been used. Do you hear how Watson almost never actually holds a note out? Maybe that’s a stylistic choice. More likely though, I think she is unable to sustain the note for very long with clarity of sound. Her breathing seems shallow which may be one reason why. She also may tend to go flat on sustained notes as I hear very minor blips toward the end of these longer notes where I think the sound producer has messed with the pitch a bit (listen to the sustained notes on "before," "people" and "say." And there's a very definite blip on "sell"). They don’t sound like the natural vocal blips of placement changes or passagi (read about that here). So can Emma Watson sing in tune? Or I guess the real question is, how far out of tune does she sing? I don’t know, because they put a band-aid on it. I can hear where there used to be a "problem" because I can hear where there is now a "fix." Is it covering a paper cut or a gaping hole? I have no idea. But shame on Disney if they’re covering up paper cuts and making young girls listen to an artificial sound that they can never hope to achieve. Because the vast majority of those girls have no idea that what they’re hearing is fake. Shame on Disney for adding artificial maturity to a voice and teaching young girls in yet another aspect of their lives they need to try and grow up sooner. Pile on the makeup, stuff your bra, and sing with a deeper voice. Because young and innocent isn’t beautiful enough. That’s what girls need to hear, right? So do I know that Emma Watson can’t sing now? Actually, as a voice teacher, I’m guessing that underneath all of that processing her voice is just fine. But that’s not the message Disney is sending. Her voice was so bad that they thought they had to rework and patch up her voice until it’s not even a truly human sound. They didn’t do that to Gaston’s voice (but then, they actually cast someone who had singing experience for his role). And in 20 years when sound processing technology has changed the difference between the two voices is going to be even weirder and more noticeable than it is today. So, thanks Disney, for sending a subliminal message of hastening maturity and setting an unattainable standard of vocal “perfection.” I’m sure girls everywhere will thank you someday. Elise is a voice teacher in Fort Collins, Colorado.

GREEK SINGING

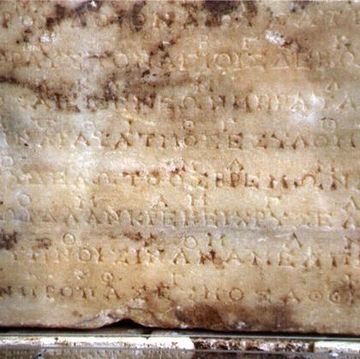

There is evidence that human cultures have almost always sung, but for our purposes I’m going to start with the Greeks. The Greeks had a complex musical system of notation which today we can't actually read; their poetry was often sung, and the video below is an example of the oldest surviving song we have by the ancient Greeks, composed around 200 B.C.

The Greeks had developed a form of theater that was sung. These works would have been performed by choruses with limited instrumental accompaniment. But again, we're not really sure what it sounded like.

MEDIEVAL SINGING

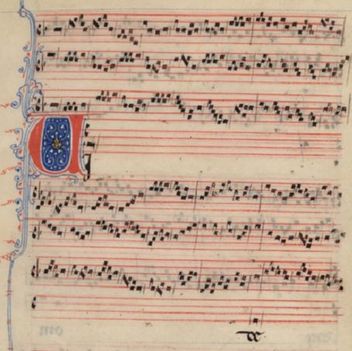

What we really recognize at modern musical notation began during the middle ages. Medieval music would have been performed in intimate settings, for groups, and by soloists. For these solos some volume would have been required, but again, the setting would likely have been small and so efficient projection and resonance not especially necessary. "Als I Lay on Yoolis Nicht" below is a medieval Christmas song. The later medieval age saw the the development of western polyphony, or harmony, in religious chanting.

RENAISSANCE

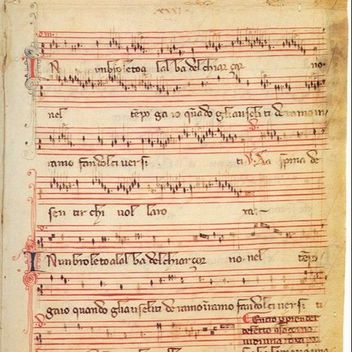

Due to the rise of harmony, the Renaissance focused largely on choral singing. This type of singing depended on the presence of multiple singers for the volume needed to fill large cathedrals (for liturgical singing) or palaces (for secular madrigals).

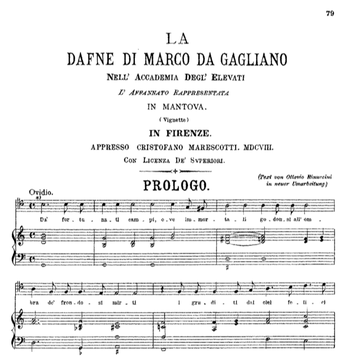

THE ADVENT OF OPERA

Opera was invented 1597, but the composers hadn't actually meant to invent a new art form. They simply were trying to recreate Greek theater. However, then as now, they didn't know what Greek theatrical music sounded like, and they idealized it. They added an orchestra and they wrote solos. Vocalists had to figure out a way to make the human voice louder or more resonant than all of the instruments. They also had to increase endurance—operas are often three hours long. That’s a long time to sing. And so the real study of the voice—and the most efficient way to use it—began. Eventually vocalists sang over more and more powerful orchestras simply by managing their vocal production with acoustic efficiency.

THE MICROPHONE

Okay, so I’m going to skip like a couple hundred years here in the interest of time, and go right to an extremely important invention: the microphone. The first microphone was built in 1870, but it wasn’t until the 1920s that it came into fairly common use in music. The microphone allowed singers to sing over all kinds of background music and be heard, no matter how they were singing. Without a microphone, this song would never have been possible:

THE DIGITAL AGE

Today we live in a digital deluge, and the impact on singing is immense. As I discuss in this blog post, much of what we hear is not actually produced by the human voice. I feel that this often leads to vocal dysphoria and an unwillingness to sing. And then there's sound compression. Do you have a friend who likes to listen to good ol' fashioned records? There a good reason for it besides image (no, really!). The sound quality of a record is MUCH higher than that of CD, and especially better than most of the MP3s that we listen to. I mean, when was the last time you actually listened to something other than an MP3? If you want more info on that, read this articlehere, but basically, layers of sound have been squished down or removed so that your music file can fit onto your phone. A lot of human vocal expression is missing in compressed files. That may be why music has become more guttural or "screamy." Screaming is one human vocal expression that survives compression. What we listen to is going to influence how sing. So . . . what are you listening to?

When I’m determining the voice type of a student, I operate under the assumption that the size and shape of your instrument (i.e. larynx and vocal tract) truly determines the type of voice you have. The size and density of your vocal folds and the size and shape of your vocal tract will determine whether you are, say, a violin or viola vocally-speaking.

Most people think your vocal range determines your voice type. The problem with this is that many people have not been trained well enough to really know what their range is. Your potential range, in addition to timbre/color and flexibility, truly determines your voice type. In a first lesson I generally will have a student slide slowly through his or her range on vowels or lip buzzes and listen for what are called “passagi.” These are the pitches where your instrument wants to switch between chest, middle, and head voice. I then rely on a sort of mélange of the Fuch system, Richard Miller’s writings on training the soprano voice, and my own experience to determine what kind of soprano you may be. So, what’s up with sopranos, and why would you want to know what type of soprano you are? The greatest advantage in determining this, I think, is the ability to sift through repertoire. There are so many kinds of soprano that it’s pretty easy to find and sing songs that don’t actually let your voice shine. An experienced teacher will be able to determine your voice type and then direct you toward pieces and roles that best suit you. Passagi can be tricky to determine in a soprano because the actual passagio may not line up with the pitches on a keyboard (it could be on either the high or low end of the F#, for example). That said, however, here’s my simplified list of sopranos and what I generally look for when classifying a voice for repertoire purposes based on my teaching experience:

After all is said and done, your passagi may not fall exactly into one of the ranges I’ve described. You may be more flexible, and able to play different types of roles. Maybe you’re just awesome like Anna Netrebko and you can go from singing Norina in Don Pasquale (coloratura soprano) to Lady Macbeth in Verdi’s Macbeth (dramatic soprano). Often a director’s vision will influence the voice type that fills a role. I’ve been in several Gilbert and Sullivan productions. Some were headed by musical theater directors and some were led by opera directors. The opera directors tend to cast me in soubrette or coloratura soprano roles, while the musical theater directors will cast me in a dramatic soprano or mezzo role simply based on my vocal weight compared to the other singers in the production. However, I still think it’s useful to know what type of soprano you are so that the pieces you choose to audition with reveal your strengths. Keep singing!

So, you've got an audition coming up. What should you do? How should you prepare? Here are five simple tips to help your audition go smoothly.

Good luck on your audition!

|

AuthorSinger, writer, mother, yogi, wife and chocolate enthusiast. Archives

January 2022

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed