|

People have been asking me about teaching children singing lessons--how do you do it? What do you do differently in a child's lesson than you would do in an adult voice lesson? Today I'll break down the structure of my voice lessons, and talk about teaching methods for children; I've also included a free printable set of cards you can use as a "game" in children's singing classes. (If you want to know why I think singing lessons for kids are a good idea, see this post).

I typically teach 30-45 minute voice lessons. Longer lessons just mean that a voice student has cultivated greater vocal endurance and is tackling more difficult repertoire, it doesn't actually impact the structure of the lesson. Ideally, my student will have sent a "practice report" notifying me of any breakthroughs or frustrations during their week of practicing. I will then structure my lesson plan around working through the difficulties and capitalizing on the momentum of the breakthroughs. The time generally breaks down like this:

When I'm teaching children I basically keep the same structure: Warm-ups, memory checks, new repertoire, and verbal review. The main difference is that I try to make everything seem like a game.

When we're reviewing repertoire, I might switch between the staccato card and the legato card. This keeps practicing from getting monotonous and teaches musical expression. When we begin learning a new song, I like to isolate melody from words (for both children and adults), so I might have my student sing through the piece on "Baa" (the sheep card) or with the tongue-extended "Ahh" (going for primal sound and a relaxed jaw). Switching between the two cards can be fun as well.

My goal with teaching children is to teach singing concepts without the child knowing they're being taught, in an organic way. I want kids to learn music and singing like they would a language. So while I do teach music theory concepts like a teacher would teach letters or numbers, I want to teach singing concepts more like a playmate would teach their friend a new word--just by playing with them. I steer clear of outright correction and instead include games to address issues that I might hear such as intonation or rhythm problems.

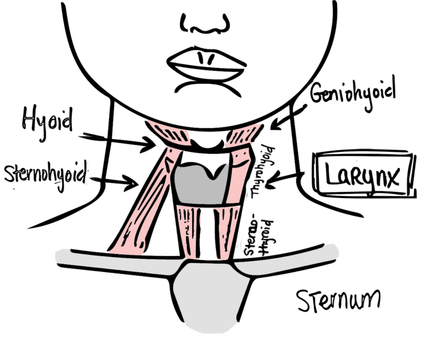

I also focus a lot on imagery (hence, all of the illustrations), and stay away from mechanical explanations or asking children to mimic me (except when teaching a truly new thing like primal sound). I've included a PDF of the game cards below. They're the perfect size to print out and glue on index cards. Or just print them on card stock and cut them out! Happy practicing!

1 Comment

I was talking to another voice teacher (actually we were texting, but for introverts like us I think it counts as a conversation, haha) and she was asking me how I deal with young singers who have totally different qualities in their lower and upper registers. It almost sounds like they have two completely different voices. She mentioned that this seems to happen more often with her young altos and mezzos than sopranos. Does this sound like you? What to know how this happens and what to do about it? Then read on!

While this system is important to singing, I mainly want you to see where and how the larynx is situated to make the next picture make more sense. This is the top view of that larynx. Now you can look inside and see where your vocal folds are situated.

So you see that there are muscles inside your larynx as well. I've essentially isolated the thyroaretnoids (T.A.s) and cricothyroids (C.T.s) in my illustration because they're the muscles that are responsible for this sense of dual vocal quality. Essentially, the C.T.s control the pitches in your chest voice, that deep part of your voice where you feel sympathetic vibrations in your chest. By contracting and releasing, they manipulate your vocal folds so that they vibrate in different spots creating different pitches. The T.A.s on the other hand control your head voice, the high pitches that might feel buzzy in your skull rather than your chest.

Now, some pitches are only going to be able to be produced by either the CTs or the TAs because they're either really low or really high. But what about all of the pitches in between? That's where it can get kind of interesting. These pitches can be produced by multiple possible manipulations; you can either favor the TAs or CTs or employ a combined manipulation of both muscle pairs. When both the TAs and the CTs are working this is called "mixed voice." Some of these manipulation options are going be healthier than others.

So, what's making that "two voice" effect? Basically it's you switching from one muscle group to another (i.e. CTs to TAs and vice versa) as you vocalize. If you're untrained, it's probably easier to just pop back and forth between the muscle groups rather than gradually transitioning to the next muscle group. Think about doing a push up and lowering yourself slowly all the way to the ground. If your muscles are under-trained, you're not going to be able to lower gradually, you'll just plop on the ground. That's essentially what's happening to your voice.

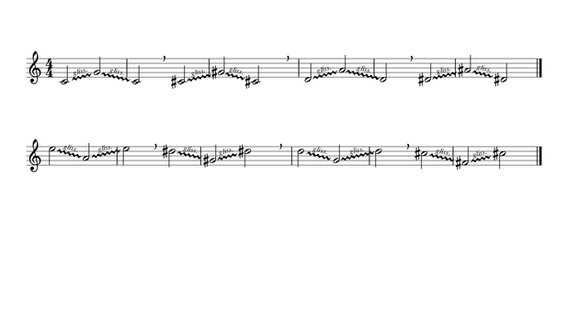

Well then, how do you fix it? You fix it basically the same way you'd fix that push-up: by repetitive exercises. Generally I find that Sopranos/tenors favor their head voices and mezzos/bases their chest voices (although not always), but basically the way to fix it is the same--you may just work from different starting points. Here's what I'd do in a series of lessons: First, I'd begin by working the voice in the less-comfortable range. This can be a little tricky, because I don't want to create tension, but the under-developed range of the voice needs to be worked out. So, I'd find a selection or two of short folk or other simple songs that are in that range. For a mezzo (or base/baritone) struggling with her head voice I might try "Love" from Robin Hood or "How Can I keep from Singing?". For a Soprano (or Tenor) who needs to work on her chest voice I'd pick something like "Are You Going to Scarborough Fair" or "Where are you going?" From Godspell. Maybe we'd just use sections of those pieces. I'd ensure those sections were tension-free and ask students to sing them every day. Often I have to reassure singers that it's okay for them to sound weak or young and remind them not to "force" a more mature sound. That sound will come as you work out your voice. It's really just the same as working out at the gym and gradually increasing your strength and endurance--if you force something too early you're asking for an injury. Next, I'd run the student through a TON of slides. Something simple like this (sing these on an "ah"):

I'd work from a comfortable range gradually moving into newer territory, depending on the voice. The KEY with these exercises is to really slide. The tendency is to skip some pitches somewhere (especially towards the end of the slide) and again just sort of "plop" onto the next pitch. If you do that the exercises won't work. You have to really hit every little micro-tone in between the pitches. Move slowly enough at first that you are sure you haven't skipped anywhere. If your voice wants to "pop" somewhere, do it again, more slowly. Once these exercises are comfortable, I'd add various vowels, maybe even work some vowel equalization (see this blog post). I have several other vocalizes you can try in mymaterials section on the website.

Unlike my straw tool, this isn't a quick fix kind of thing (although running trough these exercises with the straw is a good way to avoid tension inyour less-comfortable range). It takes consistent, correct practice to meld the two voices into one. Just be patient with your voice and gradually build up the strength you need. Happy practicing! |

AuthorSinger, writer, mother, yogi, wife and chocolate enthusiast. Archives

January 2022

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed